My civil engineer father was famous for saying “I want them to find me dead at my drawing table, like Frank Lloyd Wright” who actually died in a bed at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Phoenix, but we kept that information from Dad because it seemed petty to quibble over an aspiration that meant so much to him…the romantic American image of a man literally working himself to death. You missed an opportunity for a magazine cover there, Norman Rockwell. You might out degree my father, you might out license him, or even out engineer him now and again, but one thing you would not do…and that is out work him. That you would not do.

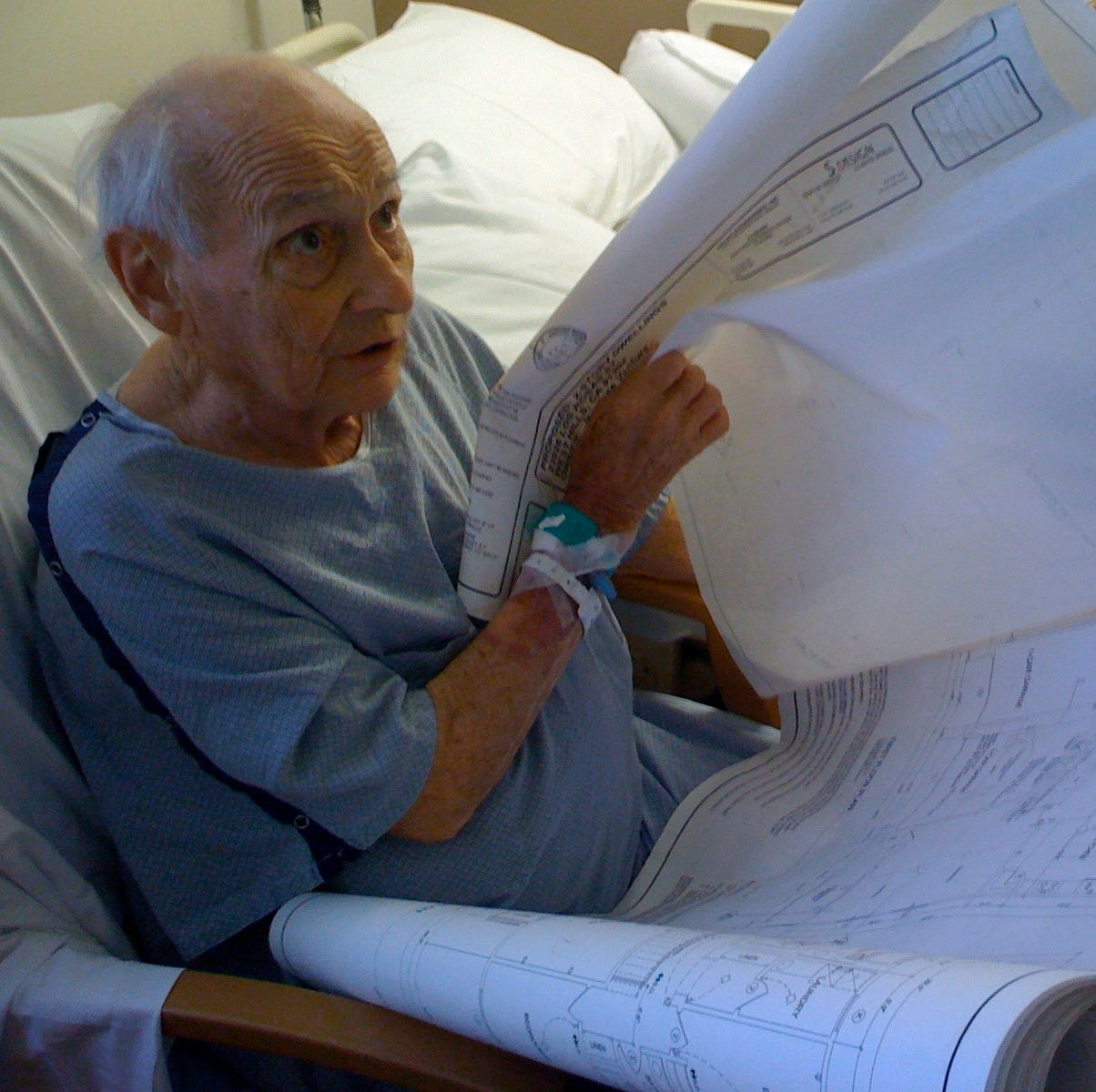

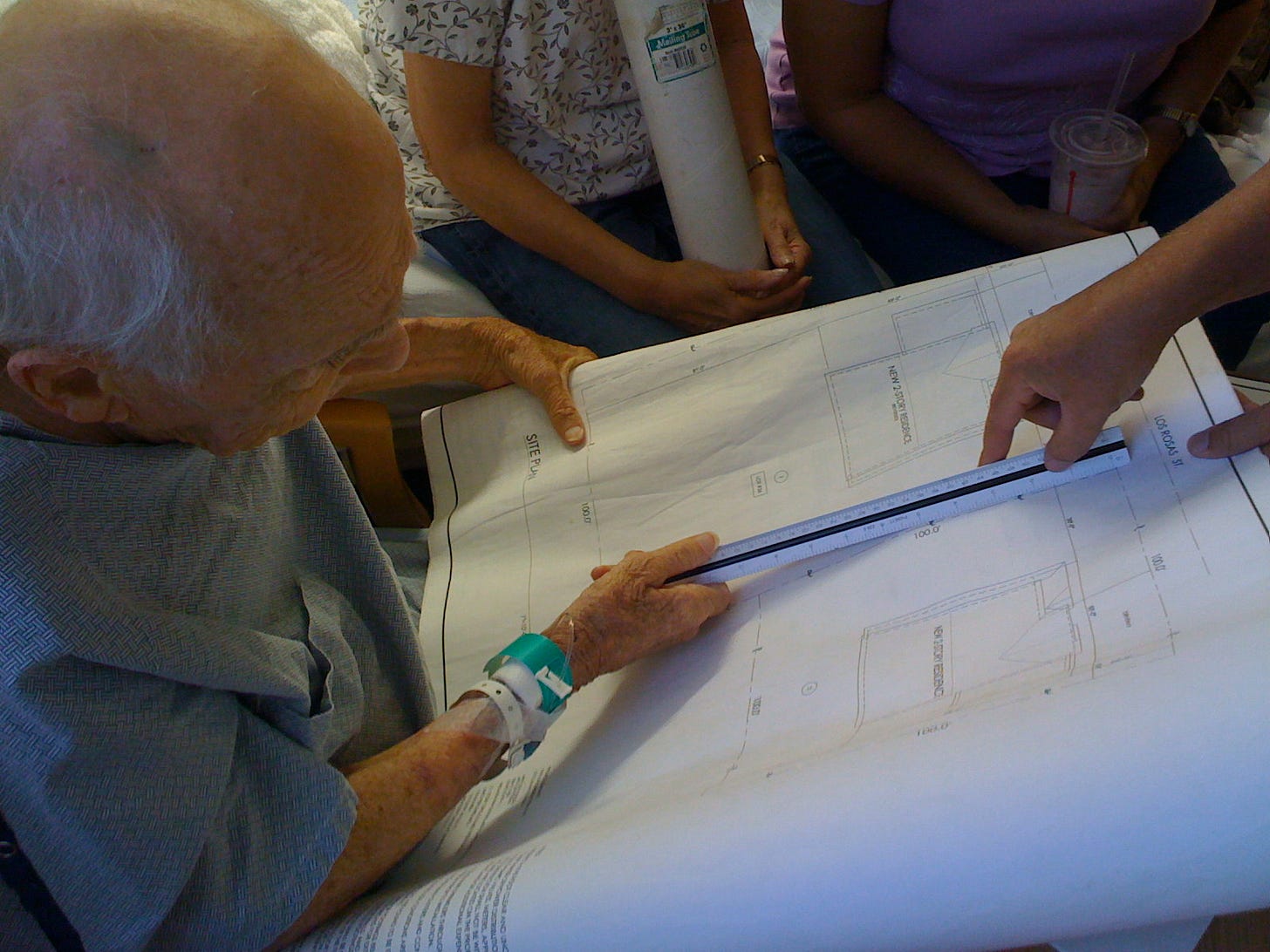

I don’t know if Frank Lloyd Wright ever worked while admitted to a hospital, but my father certainly did, while fighting off a bout with pneumonia that I think was probably exacerbated by smoke inhalation. Years ago, there were some pretty big fires out in Chatsworth at the north end of the San Fernando Valley, where his office was and I called Dad to check in. “What are you doing?” I asked foolishly, because I knew the answer. “I’m working” he said. I told him to go look out the window behind his desk and tell me what he saw. “I see fire” he said and we somehow convinced him that that was probably a bad idea, to work through a fire, and in short order he landed himself in the hospital, where he quickly earned a reputation as a possible flight risk, because he had “jobs to finish and shit to handle!” He had been in the hospital less than a day, and I came over the next afternoon to visit, but was quickly dispatched to his office, which had been spared by the flames. My father worked for himself, and rented a large room on the ground floor of a commercial complex. It wasn’t a suite, mind you…it was just a room! If you packed The Great Library of Alexandria with enough dynamite to blow the roof off, lit the fuses and ran, when the smoke cleared, you would get a sense of what Dad’s office looked like. To anyone other than my father, his office appeared to be the chambers of a madman, over stuffed cubby holes bursting with rolled up plans, bookshelves nearing collapse under the weight of engineering manuals, every single surface covered with everything from blueprints to accordion file folders to vintage survey equipment.

To the untrained eye, which was every single eye other than my father’s, his office appeared to be under a spell or some sort of curse, but not to him. “I’ve got a system. I know where everything is…just don’t touch anything.”

I was told, when I got to his office, to call him when I got to his desk and he would talk me through exactly what to bring back to his bed at the hospital. “Just put everything in a grocery bag and walk it past that God damned nurse’s station.” he told me, his voice a little weaker than usual and out of breath, but still with plenty of coal in the old furnace. And that’s what I did. At his direction, I jammed some fat file folders, some assorted loose papers and a big clipboard with a whole bunch of shit clipped onto it into a paper grocery bag I found under his desk and headed back over to the Tarzana Medical Center off of Reseda. As I approached that God damned nurse’s station, I tried to appear casual, holding the bag loosely to my chest, but desperately cradling the bottom for fear it would explode and expose my role as my dad’s job smuggler, his work mule.

I was pretty sure I was passing as just a wholesome young man delivering groceries from a local supermarket, when, without even looking up from her paperwork, the nurse on duty said: “That better not be work Mr. Kearin” I just kept walking and said: “It’s not…it’s not…” even though that bag was just chock a block with work.

When I attempted to crinkle quietly into Dad’s room, I remember he was lying on his right side, facing the door, with his eyes closed. He must have heard the bag tearing and giving way as I somehow landed all of its contents onto one of those big recliners against the wall. Without opening his eyes, he said: “Now, get that clipboard out. You see that name and number on that little sticky note near the bottom?” “Yes” I said “First thing I need you to do is to call that gentleman and tell him to fuck himself” “Okay” I said. “Anything else?” “No. That’ll do for now.” “Got it” I said.

Now, I had no intention of calling some dude and introducing myself as Gene Kearin’s son and then tell him to kindly go fuck himself, but I think me just appearing to agree to this made him feel better, and that’s all that mattered to me. I think he just liked the feeling of work in the room.

He then told me to go to the window and look down and tell him what I saw. We were up on like the 5th floor and he said he could hear what sounded like trucks down there, and not just any trucks, but they sounded like City trucks to him. Dad used to be an engineer for The City, and whatever happened while he was working for The City left a scar way down deep inside of him, so much so, that he could even identify the timbre and vibration of City equipment 5 floors up and it made him want to crawl up out of his skin. I told Dad I saw 4 big white trucks down there with writing on the doors with men in hardhats just standing around. “I knew it” he said “I knew those were City trucks” He then went on to confirm that the men were just standing around, not doing anything in particular, right? “Yes” I said “Yeah…that’s The City alright. Our tax dollars at work!” he growled.

Over the next few days, he started sitting up in bed, and with the help of his engineering protégé, my older brother Arthur, he slowly worked himself back to health. The nurses eventually just gave up, because they saw that, as the saying goes: He lived to work and worked to live, and working was actually stoking the fire inside of my father instead of putting it out. Work got him in here, we thought, and it looked like work was gonna get him out…and eventually, it did. “Take me to the office” he said.

Some of my earliest memories of my dad are of crawling around underneath the drafting table he had at home. A table he built just off our kitchen so that he could unwind after work by working, you know, just to take the edge off. My mother told me and my sisters that we all learned to walk by pulling ourselves up with the leg of the shop stool that he sat on while drawing up his plans or even using the leg of the big table itself to hold onto, before we set off across the linoleum towards the safety of crash landings on the carpeted living room floor.

Another one of my earliest memories was that of what we jokingly referred to as technically, my first job. I just remember it as a night where I was alone out in the big world working with my father and I’m thinking I couldn’t have been more than 5 years old. He took me with him one night, across the Valley and over the hill to the old CBS Radio building at Sunset and Gower in Hollywood. I remember that building very clearly because it looked so scary to me as a child, low and squat and painted black back then, with the big white CBS lettering on the side. We were moonlighting, he told me, which felt very special somehow, I was out moonlighting with my dad out in the big blue Ford, up from the Valley and through the pass, looking for that little glowing cross that floats up on that hill, that I still look for to this day, and then all the lights of Hollywood appeared off to the right, and we were off the freeway and down in the streets now, and all the people and the cars out at night, like we were traveling in a different world and the only thing close to a children’s car seat was my father’s strong Irish right arm pinning me in place whenever we stopped at any red lights on Sunset. We spoke to a guard in a shack and he let us park and we went inside and talked to another guard at a desk and we went upstairs into a big room and I stood, just a 5-year old boy, and I held the end of a steel measuring tape against the base of a wall as if my little life depended on it. First this wall, then that one, and my dad told me every time to hold on tight and I remember having to use both of my hands to hold it there, and I watched as he backed away, backed away across the room with a pencil in his teeth, and I would hear the whip sound of the steel tape dancing against the concrete floor and he would make little markings in a black book he kept in his fat breast pocket with all those other things in there, and when we were done, I let go of my end like he told me to and I watched in awe as his shoulders hunched and Dad reeled that tape back up into that round flat black case with the side crank with such lightning speed that the steel ribbon whistled a little tune and my father’s hand spun so fast your eyes couldn’t track it.

At the very end of his life, Dad told me: “I worked too hard, Stephen…I didn’t know what else to do.”